Why Attachment Styles Could Be the Missing Key to Workplace Trust

Attachment theory, a groundbreaking concept developed by John Bowlby, explores the deep emotional bonds we form with caregivers in our early years, and how those bonds reverberate through every stage of our lives. Far from being confined to family dynamics, these early attachment patterns create a blueprint for our relationships, shaping how we connect, communicate, and cope across all contexts, including the workplace.

You might wonder: what do childhood bonds have to do with job performance or how we relate to colleagues and managers? As it turns out, quite a lot. A recent meta-analysis of 109 studies found that attachment style predicts job performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and even turnover intentions. One of the most fascinating findings in this body of research is how attachment orientation influences who is most, and least, likely to stay in a toxic workplace. This often comes down to the quality of the leader-employee relationship (often expressed as trust). Put simply, the way we learn to bond early on echoes in how we receive feedback, handle stress, and commit to an employer.

The quality of our professional relationships—often described as trust—has measurable consequences. Research summarised in MIT Sloan’s management review shows that employees who experience secure, trusting relationships are 260 % more motivated, have 41 % lower absenteeism, and are 50 % less likely to seek a new job. Yet roughly one in four workers don’t feel this connection. In today’s uncertain climate, leaders need to understand that attachment theory isn’t just about trust; it explains why some people feel comfortable forming secure relationships while others feel anxious or distant. When our attachment style makes it difficult to trust others, we may be at a disadvantage in the workplace.

In this guide, we’ll explore how different attachment styles surface in professional settings, their impact on team dynamics, and actionable strategies leaders can use to foster collaboration, psychological safety, and high‑quality relationships. Whether you’re managing remote teams, navigating conflict, or mentoring employees, learning to recognise and respond to attachment patterns is not just interesting psychology, it’s a critical leadership skill for building thriving, secure workplaces.

Attachment Theory Unveiled

Attachment theory puts a magnifying glass on the formative years of our lives. It emphasizes the pivotal role of early relationships with our caregivers, typically our parents, in moulding our emotional and social development. These early bonds, or attachments, lay the groundwork for how we perceive ourselves, others, and our relationships.

Creating Mental Blueprints

Intriguingly, these early attachments create mental blueprints known as internal working models. These models are like the secret scripts that guide our beliefs, expectations, and behaviors in relationships, both personal and professional. So, whether we realize it or not, these hidden frameworks quietly influence the way we approach work relationships.

Formation in Early Childhood: These models come into existence during our infancy and early childhood. They aren't consciously articulated; instead, they're automatic mental constructs, silently shaping our perception of the world.

Beliefs about Self: Depending on our attachment experiences, we develop beliefs about ourselves. A securely attached child tends to nurture positive self-worth, while an insecurely attached one may harbor self-doubt.

Beliefs about Others: Our models also house our expectations about others. Securely attached individuals trust others to be responsive and reliable, leading to positive interactions. Insecurely attached people may expect the opposite.

Expectations in Relationships: These internal models set the stage for our expectations in relationships. A secure attachment style fuels our desire for close, fulfilling relationships, whether at home or at work. Insecure styles might hinder expectations for intimacy, trust, or dependency.

Influence on Behavior: Importantly, these models are the architects of our behaviors in relationships. Secure individuals tend to be expressive and responsive, while those with insecure styles might exhibit avoidance or dependency.

Continuity Across the Lifespan: These models are not set in stone. They can evolve as we have new attachment experiences. Yet, they often remain steady and continue to affect our behavior throughout life, including our professional dealings.

What Are Attachment Styles?

Now that we've unlocked the inner workings of these attachment models, it's time to reveal the three key attachment styles:

Secure Attachment

People with a secure attachment style feel comfortable relying on others and being relied upon. They balance autonomy with collaboration, which allows them to build positive, stable relationships at work. They trust that relationships can withstand both support and tension, which allows them to process positive and negative feedback accurately. Securely attached employees tend to contribute consistently, recover well from setbacks, and engage in constructive problem-solving.

Anxious Attachment

Those with an anxious attachment style deeply value connection and reassurance, yet often doubt whether they are truly appreciated. In the workplace, this can surface as heightened sensitivity to feedback, frequent seeking of validation from managers, or overinterpreting criticism while dismissing praise. Because they are hyper-attuned to potential threats in relationships, they tend to focus more on negative information and cues while ignoring positive information. This vigilance can make them empathetic, attentive, and highly people-oriented, but it also undermines their confidence, independence, and ability to make clear decisions under pressure.

Avoidant Attachment

Individuals with an avoidant attachment style tend to prize independence and self-reliance, often keeping emotional distance from colleagues and leaders. In professional settings, this may show up as reluctance to seek help, resistance to collaboration, or defensiveness when receiving feedback. Because closeness feels risky, they may withdraw when relationships feel too demanding. They often discount both positive and negative feedback alike, minimizing praise as well as criticism, which can make growth conversations difficult. The strength of this style is its ability to remain composed under stress and function autonomously.

In contrast, securely attached individuals lean into relationships during difficult moments, using those experiences to deepen trust and connection. Avoidantly attached individuals often withdraw emotionally when challenges arise, which limits their opportunity to build depth in relationships, reduces trust-building, and weakens overall team cohesion.

The strength of this style is its ability to remain composed under stress and function autonomously. However, their distancing can limit deeper connections, reduce trust-building, and weaken overall team cohesion.

Recognizing Attachment Styles at Work

Now that we've exposed these attachment styles, let's explore their influence on workplace behaviors:

Building Trust and Relationship Strength:

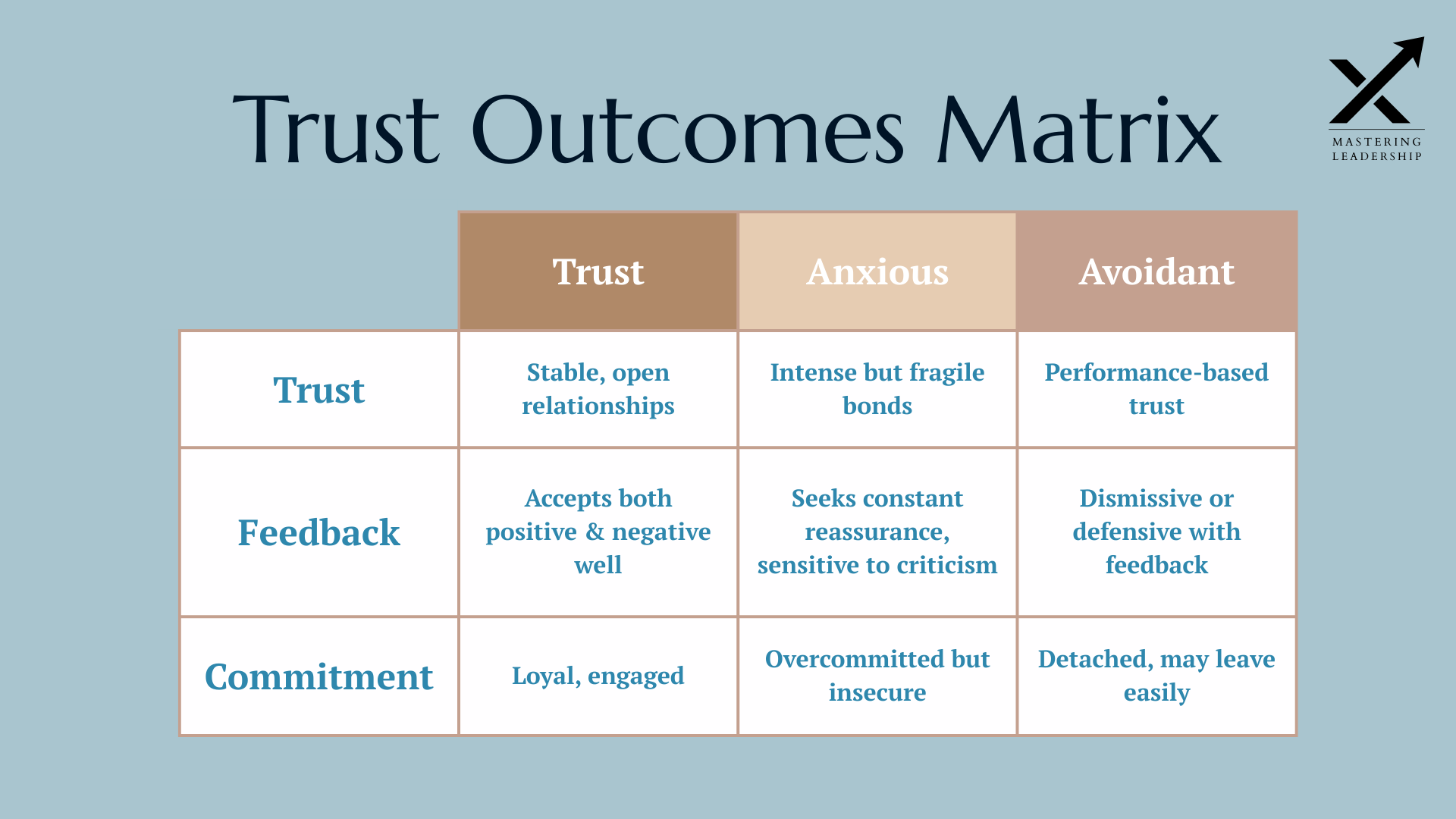

Secure Attachment: Individuals with a secure attachment style build trust through openness and consistency. They assume goodwill, balance autonomy with collaboration, and strengthen bonds during both positive and difficult moments. Their relationships are stable and enduring, marked by mutual respect and reciprocity—making them the most reliable at forming deep, lasting workplace connections. Research shows that secure attachment predicts higher levels of trust, psychological safety, and team cohesion. Teams with higher psychological safety report up to 76 % more engagement, 50 % higher productivity, and 40 % less burnout.

Anxious Attachment: Individuals with an anxious attachment style build trust through emotional investment and attentiveness, often forming intense yet fragile bonds. Their empathy and attunement foster loyalty, but difficulty with boundaries and fear of abandonment can make these relationships unstable without consistent reassurance. Their relational strength lies in genuine care for others, though relationships risk becoming draining when boundaries blur. Anxious attachment predicts greater emotional sensitivity and relational engagement, but also higher conflict and dependency when reassurance is lacking. Over time, these relationships may become draining or unstable.

Avoidant Attachment: Individuals with an avoidant attachment style build trust through competence, reliability, and respect for boundaries. For them, trust is “earned” through consistent performance rather than emotional intimacy. Their bonds tend to be steady and pragmatic, offering dependability under stress but less relational closeness than those of securely attached colleagues. Avoidant attachment predicts lower emotional intimacy but higher autonomy and composure under stress, with trust often grounded in task-based reliability. However, their strong preference for independence can reduce collaboration in teams, as they may disengage from group problem-solving and miss opportunities to deepen relationships during challenging moments.

Communication and Feedback:

Secure Attachment: These individuals are open to communication and feedback. They express themselves, both thoughts and emotions, and can give and receive feedback constructively. They don't feel threatened by feedback, so they can handle both positive and negative input effectively.

Anxious Attachment: Anxious individuals might crave constant reassurance and feedback from superiors or colleagues. They're hyper-focused on negativity because they seek security in their relationships. This can sometimes be overwhelming for thier superiors and disruptive in the workplace.

Avoidant Attachment: Individuals with this style may struggle to accept feedback and might not express themselves openly. They tend to downplay the importance of feedback because it's a form of distancing from workplace relationships. This shields them from potential relational disappointment.

Job Commitment:

Secure Attachment: Securely attached employees are likely to be committed to their job and organization. They find emotional security in their workplace, which fuels loyalty and motivation.

Anxious Attachment: While they may exhibit high commitment, anxiously attached individuals might also grapple with job-related anxiety and fear of abandonment, affecting their job satisfaction.

Avoidant Attachment: Those with this style may prioritize independence and self-reliance over job commitment. They're more likely to switch jobs or organizations without strong emotional ties.

Mentorship and Career Development:

Secure Attachment: These individuals tend to be proactive in seeking mentors and career growth.

Anxious Attachment: Anxious individuals may rely heavily on mentors for validation.

Avoidant Attachment: Dismissive individuals maintain emotional distance from others, which can impact workplace relationships and limit their career trajectory.

Leaving Toxic Work Environments:

Secure Attachment: Professionals with secure attachment styles are more likely to recognize and acknowledge toxic work environments. Their higher self-esteem and self-worth provide them with the confidence to stand up against unhealthy conditions. They possess the emotional intelligence to understand when a workplace is harmful and are willing to take action to leave toxic environments for better opportunities. Securely attached individuals also have a knack for seeking out and maintaining healthy relationships, both personally and at work, which further empowers them to break free from toxic situations with a supportive network behind them.

Anxious Attachment: Professionals with anxious attachment styles may find it challenging to leave toxic work environments due to their underlying fear of abandonment. They tend to be hypersensitive to negative cues and, as a result, may tolerate toxic conditions for extended periods. Their fear of losing their job, despite its detrimental effects, often keeps them clinging to toxic situations, seeking a sense of security in the familiar. Leaving such environments may require significant support and reassurance to mitigate their anxiety and empower them to take action.

Avoidant Attachment: Individuals with avoidant attachment styles may struggle to leave toxic work environments because of their self-reliant nature and emotional detachment. Their tendency to downplay the importance of relationships, including those in the workplace, can make them more tolerant of toxic conditions. They may not reach out for help from others, as their independence often limits their willingness to seek support. This avoidance of emotional entanglement can leave them feeling isolated and reluctant to leave, even in the face of toxicity. Breaking free may require external intervention and a shift in their perception of workplace relationships.

Final Thoughts

Attachment theory isn’t just a concept from psychology—it’s a lived reality that shapes how we show up, connect, and collaborate every single day at work. By recognizing how these early patterns echo in our professional lives, we can approach workplace relationships with deeper empathy and intentionality. For leaders, this awareness is especially powerful: it not only helps you understand your own default patterns, but also equips you to support team members in ways that unlock their potential.

Below are reflection questions to help you examine your own tendencies, along with leadership guidance framed in two ways: how to strengthen your own style, and how to best support others who lean toward that style.

Secure Attachment

Reflection question: Do I balance my comfort with collaboration and autonomy in ways that help others feel secure too?

If this is your style:

Continue modeling openness to both positive and negative feedback.

Guard against complacency, seek challenges that stretch your leadership.

Use your steadiness as a foundation for mediating conflict and anchoring resilience.

If you are leading someone with this style:

Trust them with responsibility; they tend to thrive with autonomy.

Encourage them to mentor others, leveraging their relational stability.

Provide opportunities for growth so they don’t plateau in their comfort zone

Anxious Attachment

Reflection question: How often do I seek reassurance at work, and how might that affect how others perceive my confidence?

Leadership tips:

Provide consistent, balanced feedback to build confidence and reduce the need for constant reassurance.

Create clear expectations and decision-making frameworks to ease uncertainty.

Encourage anxious individuals to reframe challenges as opportunities for learning rather than threats to their sense of belonging.

Avoidant Attachment

Reflection question: When challenges arise, do I turn to colleagues for support or withdraw—and what does that reveal about how I build trust?

Leadership tips:

Respect their need for autonomy while gradually inviting them into collaboration.

Offer feedback in private, constructive ways that reduce defensiveness.

Reinforce the value of relationships in achieving results, showing that connection is not a loss of independence but a path to impact.

Further Reading

Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume I. Attachment. Basic Books, 1969.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. 2nd ed. Guilford Press, 2016.

Yip, J. A., Ehrhardt, K., Black, H., & Walker, D. O. “Attachment Theory at Work: A Review and Directions for Future Research.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 2018, 185–198.

Richards, D. A., & Schat, A. C. H. “Attachment at (Not to) Work: Applying Attachment Theory to Explain Individual Behavior in Organizations.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 2011, 169–182.

Harms, P. D. “Adult Attachment Styles in the Workplace.” Human Resource Management Review, 21(4), 2011, 285–296.

Game, A. M. “Workplace Attachment Styles and Burnout: A Person-Centred Approach.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(8), 2011, 1902–1920.